It’s almost noon, and University of Surrey PhD student Ieuan Matthew Carney and five of his peers are having breakfast with Etlaq Spaceport staff at their headquarters in Muscat, the capital of Oman. They pepper their hosts with questions, perhaps too many, about the company’s philosophy and the hardware they use.

“We were quite chuffed that some of the kit they use was very similar to what we got our hands on at Surrey when we were building our payload,” remembers Ieuan. “What I remember most about that visit was just how accommodating they were and their patience with our questions – they let us see the launch pad infrastructure, where they work – I honestly can’t remember them saying no to anything. It was a great experience.”

Mission Ready

The group were in Oman in June 2025 as part of JUPITER, the Joint Universities Programme for In-orbit Training, Education and Research. Backed by Space South Central (a thriving industry cluster that is driving collaboration amongst universities, private industry, SMEs and government to ensure space is at the forefront of economic growth in the region) the initiative brings together students to design, build and launch their own satellite hardware. Their project, Jovian-O, carried DAVE, an Earth-observation instrument that the team hoped would capture pictures of Earth and even spot space debris, all released from a student-designed deploy pod built at Surrey.

From Muscat, they began their 571km drive to Duqm, a port town on the Arabian Sea coast and home to Etlaq Spaceport. For the next three weeks, the students worked side by side with Stellar Kinetics and Etlaq engineers, testing their payload, rehearsing integration, and experiencing the full reality of life at a spaceport.

In the end, the rocket did not launch. For many teams, that might have been the lasting memory. But for Ieuan and his peers, the experience was far from wasted. "When we got back home, yes I was gutted, but honestly I was champing at the bit. I wanted to use this first-hand experience, this new confidence that I just obtained," says Ieuan.

"The UK space sector faces a well-known shortage of skilled engineers, and programmes like JUPITER are designed to close that gap," comments Professor Keith Ryden, Director of the Surrey Space Centre at the University of Surrey. "These six students came back better prepared, with practical skills and a stronger sense of what a career in space can look like. They may not have seen their satellite fly this time, but they came home mission ready."

Myths and legends

You could trace Ieuan’s experience to that of another young postgraduate student at the University of Surrey was questioning everything about how space engineering should be done.

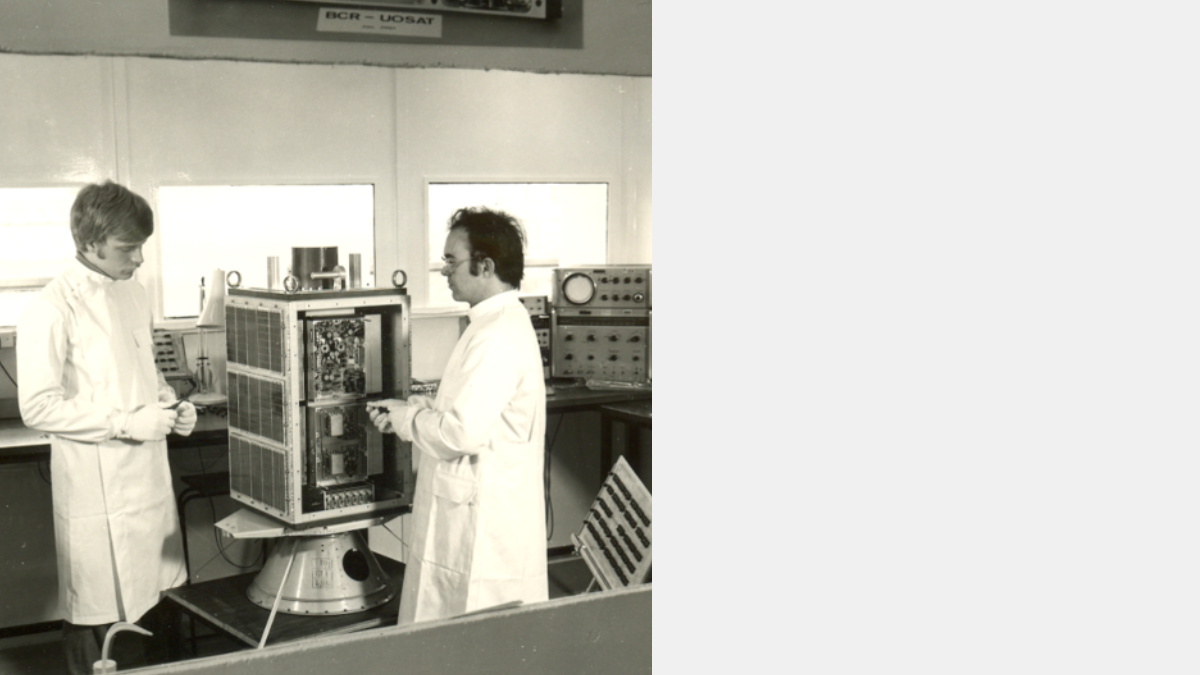

“We didn’t have any money but we were incredibly ambitious,” says Professor Sir Martin Sweeting. “I didn’t see why satellites had to be these vast, expensive machines built only by states, with billion-pound budgets.”

Armed with off-the-shelf components and circuit boards laid out on a kitchen table, Sir Martin designed and assembled a small satellite in a campus lab.

“I was convinced we could break the mould,” he insists. “By using modern microelectronics and building smarter, smaller satellites, we could make space more affordable, more responsive, and open it up to nations, organisations and people who had never dreamed they could take part.”

In 1981, UoSAT-1 launched into orbit with NASA’s help – the world’s first modern small satellite. Just four years later the success of that mission had helped pave the way for Sir Martin to found Surrey Satellite Technology Ltd (SSTL), a university spinout which became a global leader in small satellite technology. Sir Martin also went on to establish the Surrey Space Centre, bringing together research, teaching and innovation in space engineering on campus.

“The story of Sir Martin has reached near mythical proportions,” says Professor Keith Ryden, current Director of the Space Centre. “His story continues to inspire students and academics at Surrey, but its impact also continues to ripple out across the entire space sector.”

Today, Sir Martin remains Executive Chairman of SSTL and is a Distinguished Professor at the University of Surrey.

Evolving legacy

Four decades after Sir Martin launched the Surrey Space Centre, the University's legacy in space engineering and space-related research is now evolving into something larger and more ambitious – the Surrey Space Institute.

"We bring together expertise from across the University to tackle the most urgent challenges in the global space sector," says Dr Lucia Fonseca de la Bella (pictured), one of the team behind the new Surrey Space Institute. "Yes, space engineering remains at the heart of the Institute, but today’s space economy is shaped by law, business, biosciences, AI, materials science and more.”

"More than 30 Surrey academics are already active in space-related projects, alongside colleagues in the Space Centre."

The Surrey Space Institute is working across three themes: Water on Earth – using satellites to manage water and climate, support agriculture and protect natural resources; Space infrastructure and resilience – strengthening critical systems such as communications, navigation and cybersecurity; and Deep space exploration – advancing technologies and legal frameworks for sustainable exploration of the Moon, Mars and beyond.

This breadth reflects the diversity of Surrey’s research. In law, colleagues are shaping the regulatory frameworks for sustainable space activity. In business and tourism, researchers are examining the opportunities and risks of a growing commercial space economy. In physics and engineering, Surrey academics are developing technologies to reduce satellite light pollution, build deployable structures and design advanced propulsion. In biosciences and psychology, researchers are studying health, performance and wellbeing in space environments.

"Together, these efforts show how Surrey can apply space science to real-world problems while preparing for human activity beyond Earth," says, Dr Fonseca de la Bella.

The Institute also has a clear role in addressing the UK’s space skills gap. With the national sector now worth £18.9 billion and supporting more than 52,000 jobs, demand for trained professionals far outstrips supply. Surrey aims to train 10% of the UK’s future space workforce through postgraduate courses, professional training and live mission experience.

By offering hands-on learning, like that experienced by Ieuan and his colleagues on the Jovian-O mission, alongside academic study, the Institute will ensure that students graduate ready to contribute to industry from day one.

“Space is no longer a frontier activity; it is already a critical infrastructure underpinning everything from climate security to high-speed connectivity,” says Professor Adam Amara (pictured), inaugural Director of the Surrey Space Institute and Chief Scientist to the UK Space Agency. “By uniting Surrey’s 45-year leadership in small satellites with cutting-edge AI and cyber-resilience, we can give the UK the decisive capability it needs to continue to lead in space sector innovation and to solve complex problems at home and around the world.”

Looking ahead

For Ieuan, the experience in Oman was only the beginning. “I came back with a much clearer idea of where I want to go,” he says. “Working side-by-side with engineers at Etlaq and Stellar Kinetics showed me that I can contribute at that level, and it gave me the confidence to push further in my own research.”

So, what comes next for Ieuan? “I want to stay in the UK space sector, help it grow, and be part of the teams that make sure we can launch missions here at home. We have the talent and the technology – I’ve seen it first-hand – and I want to play my part in building that capability.”

As the UK space industry continues to expand, Ieuan and other Surrey graduates will be among the new generation of engineers turning experience into leadership. Their journey reflects Surrey’s wider ambition: to give students the skills, the networks and the opportunities to shape the future of space. Through the Surrey Space Institute, the University will build on this legacy – driving research, supporting space SMEs and preparing the workforce the sector needs to thrive.