A Reflective Practice Framework

Working to encourage and support reflective practice across the University of Surrey

Here at Surrey, we are firmly committed to ensuring that all our staff and students feel supported, and we endeavour to provide a range of services that will enable you to promote your health and wellbeing. Below, we explore our new Reflective Practice Framework, created by our Centre for Wellbeing team.

This new resource is for staff to access so that you can incorporate into your roles. The framework is mainly aimed at managers and team leaders, but can also be used by teams in general to encourage and support reflective practice.

This overview explains what reflective practice is - and how to do it.

What is Reflective Practice?

Reflective practice represents a systematic approach to reflection that involves creating a habit, structure, or routine around reflecting on our experiences.

Reflective practice can be an individual and a collective experience. Choosing to learn from experience as an individual or with colleagues depends on the purpose of your reflection and your learning agenda. For example, if you need to make sense of a week’s worth of meetings, frustrations, and turning points in order to decide how to proceed with a project, then you might choose to explore these individually first before discussing your thoughts with your colleagues. If, on the other hand, you wish to consider your role in an experience of conflict, you may choose to do this alone.

Among the most powerful tools for reflective practice are questions, stories, and dialogue. Because reflective practice is structured around inquiry, questions are key to effective reflective practice. Stories (narrative accounts of experience) enable us to “re-live” an experience. Tools such as “Critical Incident Technique”, journals and diaries can be useful ways of revisiting our own stories of the experiences we have had. By examining the way we have constructed our narrative account about a significant event we begin to get insights about the meaning we have given to that experience. These can be further explored individually through the use of carefully chosen questions or can be examined with colleagues through dialogue.

Reflective practice can help teams to:

• Uncover new information: by sharing ideas with others, individuals’ memories can be triggered, and new information and more refined insights can emerge .

• Limit biases: a thorough and critical discussion about information (impressions and data) means it is cross-checked and people can point out when they feel an issue has been represented inaccurately.

• Build a clear picture of a situation/event/process and reach consensus: by discussing data, contradictions, and gaps, these can be understood or filled.

• Ensure well-reasoned, meaningful actions: joint analysis can reveal the structural causes of problems and solutions.

• Facilitate action that has broad ownership: the more people that understand the causes and extent of issues, the more this can motivate people to invest in making change happen.

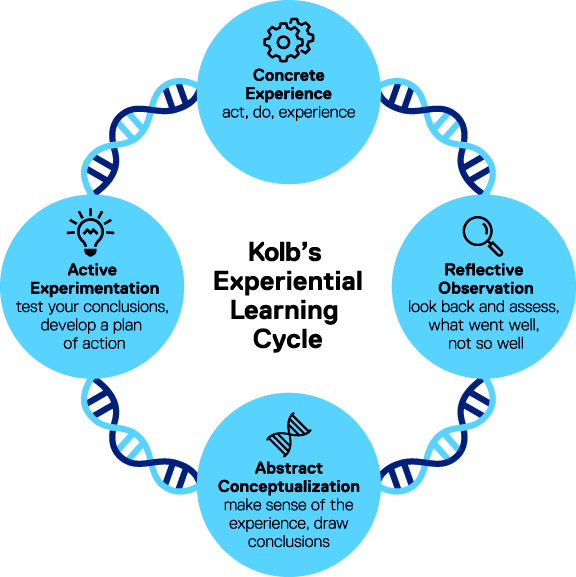

The Experiential Learning Cycle

The model for reflective practice is based on the cycle of experiential learning developed by Kolb (1984). The experiential learning cycle involves four stages: Concrete Experience (Acting), Reflective Observation (Reflecting) Abstract Conceptualisation (Learning) and Active Experimentation (Planning).

Acting involves doing something. This may be something deliberate and intended or something unintentional. The intended action may work out as planned or not.

Reflecting involves returning to the action, re-examining, and making sense of it.

Learning involves generalising from the experience and making connections with our existing knowledge and experience in order to improve future action.

Planning is the link between past experience and future action. It involves using your learning to predict what needs to happen to achieve your goals.

The Process of Reflection

Reflection is an active process of witnessing one’s own experience in order to examine it more closely, give meaning to it, and learn from it. It involves three elements:

• Returning to experience: Recalling or detailing salient events

• Attending to feelings: Using helpful feelings and removing or containing obstructive ones

• Evaluating experience: Re-examining the experience in the light of one’s intent and existing knowledge and experience. It also involves integrating this new knowledge into one’s conceptual framework.

“Reflection is not casual. It involves wondering, probing, analysing, synthesising, and connecting. And not just about what happened but why it happened and how it differs from other happenings”

The benefits of reflection are that it:

• Enables individuals to think more deeply and holistically about an issue, leading to greater insights and learning.

• Connects the rational decision-making process to a more effective and experiential learning process.

• Challenges individuals to be honest about the relationship between what they say and what they do.

• Creates opportunities to seriously consider the implications of any past or future action.

• Acts as a safeguard against making impulsive decisions.

Schön (1983) describes two main types of reflection:

Reflection in action: is the way that we think and theories about practice while we are doing it. It involves bringing what are often subconscious processes into the conscious mind and being more aware of what we are doing and why in the moment. This is why reflection in action is sometimes called “thinking on our feet”.

Reflection on action: involves us in consciously exploring experience in retrospect. It assumes that the practice is underpinned by knowledge. Reflection on action is therefore an active process of transforming experience into knowledge and involves much more than simply thinking about and describing practice.

Although both reflection on action and reflection in action can be part of reflective practice, it is reflection on action that is the core component of team learning in reflective practice.

Facilitating a Reflective Practice Group

Facilitating reflective practice groups is a skill. Not only do you need to ensure that all members of the group are engaged, but you also have to self-regulate your own responses to allow the group to take the journey, as opposed to being led by you as a guide. The following model represents an outline for the facilitation of a reflective practice group.

Resources

Facilitators should consider the following resources essential:

* A suitable room for group discussion, which is quiet and easily accessible.

* Pens, paper and white board

* 60 - 90 minutes designated time for facilitation

Opening the session & ground rules

At the beginning of the session, tell members how the group will run and explain the ground rules for engagement and your role as facilitator.

Ground rules or agreement

“I” Statements: Our tendency to use second person statements can impact participation in reflective practice. Not only can it be an example of projecting one’s personal context onto someone else, but it also limits the power of the speaker using their own ‘voice’.

Talk to the group: There can be a tendency for members of the group to talk to the facilitator and not to other members of the group, even seeking the facilitator’s approval or concurrence. This can make groups members feel uncomfortable if they perceive their comments/perspective will be judged as “right” or “wrong” based on the degree to which they align with those of the facilitator(s).

Emphasise the degree of confidentiality they can expect: If the conversation has any chance at all of addressing personal or professional issues, it is essential to address this at the outset. Be explicit about what (if anything) can and what cannot be shared outside the group. In reflective practice, the expectation is that (aside from comments about potential harm to self or others) what is said in the group, stays in the group.

Emphasise the value of everyone participating in the small group and that there are no “right” or “wrong” answers: Small group discussion affords learners the opportunity to express themselves verbally and perhaps most significantly, offers learners the opportunity to benefit from the perspectives of others. As such, it is important that each member contribute the discussion – as much for the benefit of others as for any other reason. Important note: Some participants will contribute a small amount to the conversation in a verbal form, but their non-verbal communication can demonstrate engagement and is completely appropriate.

Explain your role: Remind participants that you are not here to ‘solve their problems’ or offer ‘solutions’, the group may arrive at solutions, however your role is to facilitate the reflective discussion.

Talk less: In the first few minutes, you are likely to do quite a bit of talking as you set the ground rules. This can demonstrate a pattern of the facilitator talking a lot and the group talking very little. It is essential that you explicitly state that once you finish setting the stage, members of the group will spend most of the time doing the talking.

Discussion management strategies

Desired outcomes: At the beginning of the session, ask each participant what they want to get out of it. This will help you to identify how you can best help them (individually and as a group) to reach their goal, and also gives you the opportunity to emphasise the added value that small group discussion offers. Namely, the opportunity to express themselves and to benefit from the perspectives of others.

Decide on a topic: Agree as a group on a topic for the reflective practice session. Remember too broad a focus can make it difficult to give the topic the attention it needs and might be hard to give direction to the reflection.

Managing conversation domination: When a member or a small group of members dominate the conversation, others might contribute less than they otherwise would. In addition, those dominating the conversation lost the opportunity to hear others’ perspectives. This behaviour can stem from people having strong feelings about the topic, but it can also stem from an anxiety about the topic and a desire to not have to confront an internal sense of ambiguity about how to handle a situation. Explain that the value of small group is in offering the opportunity to listen to others’ perspectives. When this alone does not suffice, some example question that may be helpful include:

Derailing the dialogue: You will likely encounter learners whose comments may appear tangential or even unrelated. Before assuming their comments are unrelated to the discussion, pause, see where they are going, and give them the benefit of the doubt.

If the comments repetitively derail the conversation, you may need to be more directive to keep the conversation on track.

Insensitivity: In most situations, insensitive comments are not intentional, but that does not necessarily make them any less painful. There are times when you will feel the need to step in, but I encourage you to give the group the space to address the insensitivity – in most cases, others will challenge the insensitive comment, and peers redirecting the offender can be far more helpful in affecting long term behaviours and establishing social norms than the facilitator stepping in. If this does not happen, call out both the individual to explain their comment and the group, emphasising the responsibilities we each have as a member of our community.

Closing the session

Summarise what the group has discovered: As the facilitator, helping the group to see where they have come during the course of their discussion can be very helpful. This frames the experience and help group members make and cement connections between concepts discussed. Thereafter asking them how they might approach similar challenges in the future, and writing those down, can be very valuable for each member of the group.

Offer your own narrative: Sharing personal experiences related to the topic in question, describing the challenges you faced and how you dealt with them can help learners make connections between concepts discussed and real-life scenarios. This is particularly valuable when your learners are relatively inexperienced in the area being discussed. Offering this towards the end of the session is important so as not to suggest that your response is the ‘right’ one.

Reiterate confidentiality: This reinforces group expectations and supports the safety of the learning environment.

Provide a way to communicate with you after the session: If you are comfortable doing this, you will find that many of your learners reach out to ask follow-on questions after the session. It can be helpful to provide a safe and manageable space to do this.

Facilitating the session beginning to end

The most important role of the facilitator is to help keep the discussion going. In order to do this, here are a few points to keep in mind:

*Remember your goal, but remain open – What do you want members to leave the meeting with? A skill? Knowledge?

* Stay focused on your goal - If you notice the meeting is going in another direction, try to bring it back. However, don’t be so strict that you ignore valuable learning moments.

* A good reflective practice meeting is one that helps people think and grow.

Maintaining consistency: regular reflection

The support embedding reflective practice into daily practice make sure to schedule regular reflective practice sessions. If you can decide on a regular day and time to facilitate your sessions. Book the sessions well in advance so people can schedule them into their diaries. Even if attendance is low it is still important that you continue the session as planned, this way your encourage the creation of a safe, reliable ‘container’ for reflection.

Critical Incident Technique

The critical incident reflection technique offers an alternate approach to reflective practice focussed on a specific incident. This can be used as a stand-alone session following an ‘Incident’ or as part of the regular reflective practice session.

Introduced by Flanagan (1954) suggested critical incident reflection to achieve the following goals;

1. To formulate problems in general terms so that they could apply findings to a broad range of issues.

2. To emphasise new research methods to be of central importance.

3. To develop “the critical incident technique” to identify contributing factors to the success or failure in specific situations.

Analysing a critical incident can help individuals to:

• “reflect-on-action” (ie past experience),

• “reflect-in-action” (ie as an incident happens)

A critical incident reflection framework

The framework below is a guide for your own reflection and learning from events that have significance to you. The questions under each heading are “prompts” only. The framework is there to support you identify and develop options. There are no right or wrong responses although the overarching frames of “The what?”, “So what?” and “Now what?” are important components in a critical incident reflection.

The what?

A description of the incident/experience with just enough detail to support doing your “So what?” section. For example, description about who, what, why, when, where.

So what?

This is the sense-making section that asks you to surface general meaning, significance, your position / view point; actions; emotions (pre-during-post). Now what?

This section makes connections from the experience / incident to further actions. For example, what would you do differently / the same next time? How come? What are key points, lessons learnt to share with your colleagues, network and/or group outside the network? (eg. idea, product, process, concept)? How will you do this?

Reflective questioning examples

The following questions can be used to trigger useful reflection about a situation, problem, or challenge. The three types of questions are designed to focus attention on a situation, connect ideas and find deeper insight, and create forward movement.

Questions to focus attention on a situation

1. What question, if answered, could make the most difference to the future of (my/our specific situation)?

2. What is important to me/us about (my/our specific situation) and why do I/we care?

3. What draws me/us to this inquiry?

4. What is my/our intention here? What is the deeper purpose (the big “Why”) that is really worthy of my/our best effort?

5. What opportunities can I/we see in (my/our specific situation)?

6. What do I/we know so far or still need to learn about (my/our specific situation)?

7. What are the dilemmas and opportunities in (my/our specific situation)?

8. What assumptions do I/we need to test or challenge in thinking about (my/our specific situation)?

9. What would someone who had a very different set of beliefs than I/we do say about (my/our specific situation)?

Questions to connect ideas

1. What is taking shape? What am/are I/we hearing underneath the variety of opinions being expressed?

2. What is emerging here for me/us?

3. What new connections am/are I/we making?

4. What had real meaning for me/us from what I/we have heard?

5. What has surprised me/us? What has challenged me/us?

6. What is missing from this picture so far? What is it that I/we am/ are not seeing? What do I/we need more clarity about?

7. What has been my/our major learning, insight, or discovery so far?

8. What is the next level of thinking I/we need to evolve to?

9. If there was one thing that has not yet been said in order to reach a higher level of understanding and clarity, what would that be?

Questions to seek focus

1. What would it take to create change on this issue?

2. What could happen that would enable me/us to feel fully engaged and energized about (my/our specific situation)?

3. What is possible here and who cares? (Rather than “What is wrong here and who is responsible?”)

4. What needs my/our immediate attention to move forward?

5. If my/our success were completely guaranteed, what bold steps might I/we choose to take?

6. How can I/we support one another in taking the next steps? What unique contribution can I/we each make?

7. What challenges might come my/our way and how might I/we meet them?

8. What conversation, if begun today, could ripple out in a way that created new possibilities for the future of (my/our situation)?

9. What seed might I/we plant together today that could make the most difference to the future of (my/our situation)?

If you have questions, or require further help, please contact the Centre for Wellbeing's Training Lead & Wellbeing Advisor, Hugo Metcalfe, via h.metcalfe@surrey.ac.uk