Returning to research

How two University of Surrey scientists came back to work

It’s true that people often find their jobs meaningful.

But how many of us can say our work is truly life changing?

More so, how many of us have the staying power, passion and commitment to keep pushing boundaries.

Two scientists at the University of Surrey fit this category.

Dr Lisa Mohebati

Dr Lisa Mohebati

Professor Margaret Rayman

Professor Margaret Rayman

Their research is so current that it begs the question, what would we not have known if these returners to research had never come back?

Both came back to the lab thanks to help from the Daphne Jackson Trust.

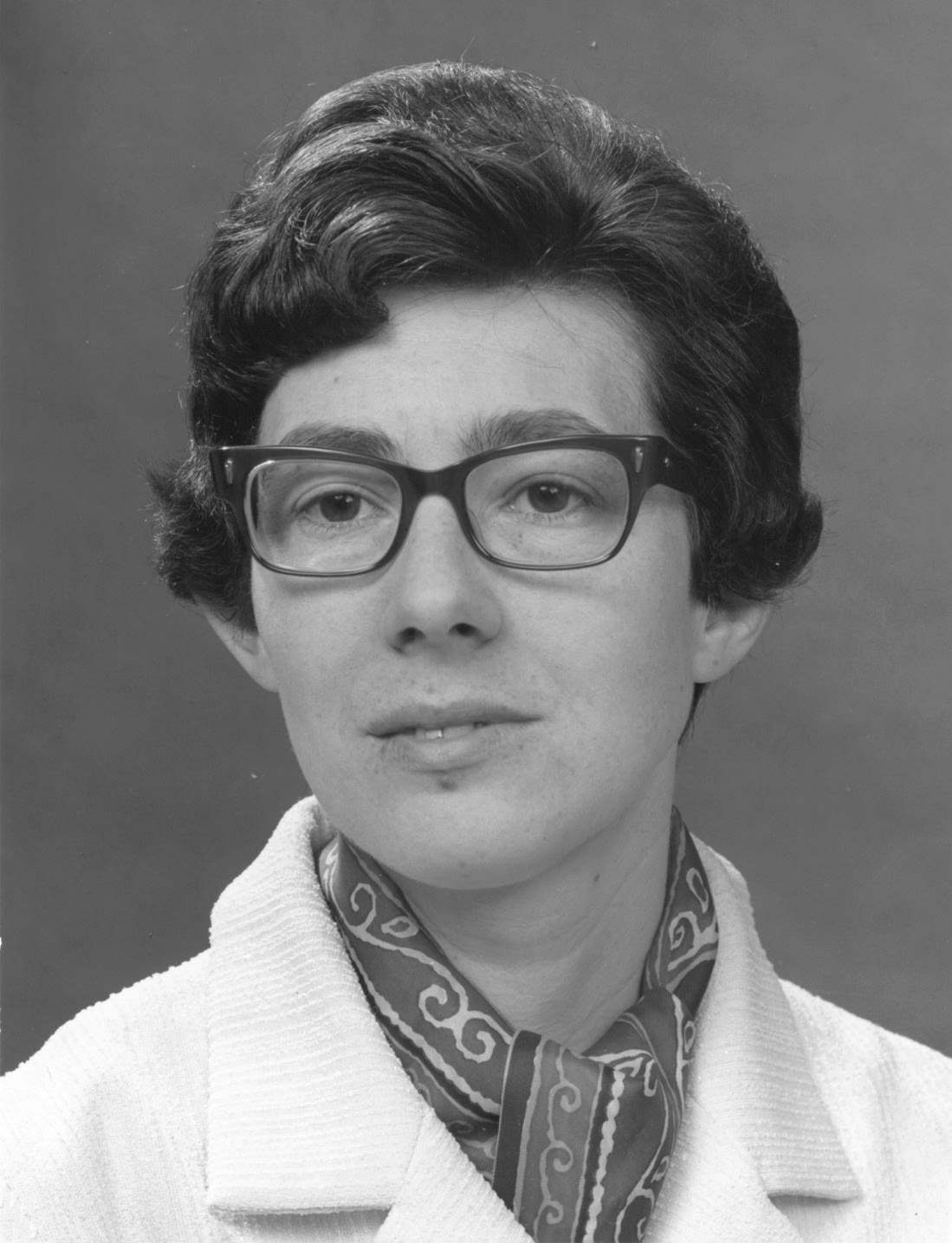

The Trust is named after the first female physics professor in the United Kingdom, who in 1986 established a pilot program upon which today's fellowship is modelled.

The Daphne Jackson Trust

Daphne Jackson graduated in Physics from Imperial College in 1958. She moved to Battersea College of Technology (now the University of Surrey) where she began her research career in theoretical nuclear physics. She was awarded a PhD in 1962.

Professor Jackson was appointed Professor of Physics at the University of Surrey in 1971 – the first female Professor of Physics in the UK.

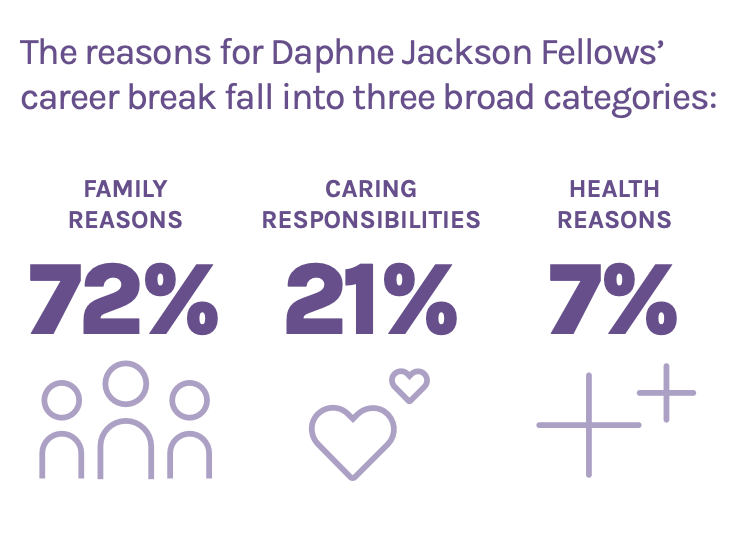

It has so far helped 480 researchers return to science after a career break of two or more years due to personal circumstances.

The Trust now also helps research across the arts, social sciences and humanities.

The fellowship aims to address the problem that "many people who have trained in science, technology, engineering, and mathematics and worked for a number of years in research … struggle to return after a career break.”

Professor Margaret Rayman is one of the Surrey returners.

Professor Margaret Rayman is a world leader in nutritional science who set up and still helps to run the UK’s only MSc in Nutritional Medicine at the University of Surrey. Her research interests include the role of the micronutrients, selenium and iodine and in particular the role of selenium in combatting viral disease and thyroid problems.

Professor Margaret Rayman is a world leader in nutritional science who set up and still helps to run the UK’s only MSc in Nutritional Medicine at the University of Surrey. Her research interests include the role of the micronutrients, selenium and iodine and in particular the role of selenium in combatting viral disease and thyroid problems.

“I want to improve the lives of people and communities and in particular to help pregnant women to have healthy children with the best opportunities in life.”

She is one of eight of the Fellows helped by the Daphne Jackson Trust to have gone on to become professors in UK Universities. Four of them – Professor Hilary Hurd, Professor Margaret Rayman, Professor Andree Woodcock and Professor Pia Ostergaard continue their research today.

Professor Rayman is now in her 70s and despite a 20 year gap - much of which was spent designing kitchens - she is again at the forefront of nutrition.

She has contributed to pre-natal nutrition, with her research into the effects of lack of iodine in pregnancy reducing cognitive abilities in children.

Iodine deficiency is a growing threat - and one that could result in the 'cognitive underperformance of communities at a large scale'.

UK pregnant women are not eating enough iodine-rich foods such as milk and cheese, hampering adequate brain development of their babies.

Her research is also playing a key role in helping those choosing a vegan diet to understand dietary deficiencies which could lead to bone fractures or even stroke.

She collaborates globally with colleagues in Denmark, China and the US.

“People choose a vegetarian or vegan diet for a number of reasons,” she says.

Photo by Louis Hansel on Unsplash

Photo by Louis Hansel on Unsplash

“At the moment, many are making that change for environmental reasons and people believe it is a healthy diet.

Photo by Diana Polekhina on Unsplash

Photo by Diana Polekhina on Unsplash

"And that's for good reason. Research over many years has linked plant-based diets to lower rates of heart disease and type 2 diabetes.”

A new study, published in the medical journal The BMJ, raises the possibility that despite the health benefits demonstrated by past research, plant-based diets could come with a previously unrecognised health risk.

Following a vegetarian (including vegan) or pescatarian diet is linked to a lower risk of developing heart disease than eating a diet that includes meat, research has found.

“Bone fracture is linked to the intake of calcium and vitamin D,” adds Professor Rayman.

Photo by engin akyurt on Unsplash

Photo by engin akyurt on Unsplash

“Vitamin D is low in most people, not just vegans, but anyone who doesn't eat milk or dairy products may well be short of calcium.

“There are some other aspects of milk that may possibly be relevant: casein, a milk protein, is important for infant bone elongation and production of insulin is stimulated by whey protein,” she adds.

“We know that some breakdown products of milk proteins and also n-3 long chain-polyunsaturated fatty acids (EPA and DHA) can reduce blood pressure which is an important risk of stroke.

“Vegans would not normally eat milk/dairy products or these fatty acids which come from fish.

“Daily doses for 8 weeks showed blood-pressure reductions which were clinically meaningful which, at a population level, could be associated with lower cardiovascular disease risk,” she says.

“A small, reduced risk of hypertension that could be important at a population level was associated with a 200 g increase in dairy products (excluding butter),” she explains.

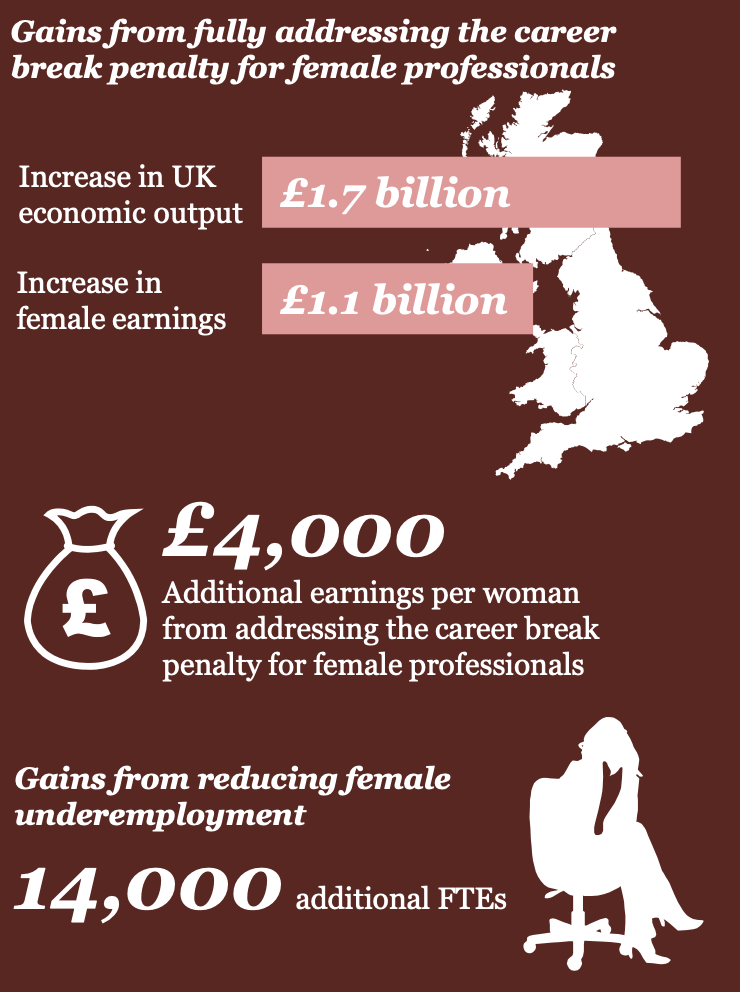

One of the leading lights in helping individuals return to the lab is Dr Katie Perry. She is the Chief Executive of the Daphne Jackson Trust – whose work to realise the potential of returners to research careers after career breaks taken for family, caring or health reasons has just been recognised with the Royal Society Research Culture Award 2023.

"The majority of us think of researchers as being super-human, squirrelled away in a lab, working tirelessly day and night as they inch towards their ‘eureka!’ moment," she said.

"But if you ask anyone that has worked in research, they will probably tell you the reality is very different. Researchers are people, just like you and I, and we all have lives inside and outside of work that shape what we do, where we do it and how we work.

"In research, there’s a pervasive expectation that every researcher should follow a linear path... completing University, gaining their first position in a lab to eventually reaching fruition decades later as a fuzzy-haired Professor. But life isn’t always so linear – and many researchers take unexpected turns in their work and personal lives that don’t follow traditional ‘norms’. "

Career breaks happen surprisingly often. Some are short and specific, such as a gap between grants, or pivoting research interests and switching to a new field. Others are longer and might be related to having a family, caring for a relative or dealing with a health issue.

Katie is a physicist with a background in science communication and holds a degree and PhD in Physics from the University of Surrey. In 2022, Katie was awarded an honorary degree by the University of Surrey in recognition of her commitment to securing the legacy of Daphne Jackson’s vision – supporting research returners.

Dr Katie Perry

Dr Katie Perry

"For the UK to continue the path to becoming a science superpower I would like to see further investment in the almost untapped talent pool of researchers that have diversified off the linear path. A portion of the funds delivered to the UK Science and Technology Framework should be going to those that support the return and retraining of the already incredible talent pool we have in the UK," she adds.

“Returning is a great idea but be prepared to work very hard or you won’t get anywhere,” says Professor Rayman.

“I left research because I was pregnant and working in a lab with carcinogens which could affect the placenta,” she explains.

“I taught for three years before having a second child and moving to France.

“I went back into research some 20 years after I had left it. In the meantime, I spent 7 years in France with my husband and children. When I came back to Surrey, I designed my own kitchen and found a joiner to make it. That gave me a new part-time career which worked with the children and a husband who was travelling a lot of the time. I designed and drew the plans for kitchens and bathrooms made out of recovered wood which were made by that same joiner.

“When the children were a bit older, I thought it would be good to go back and that is when I found the Daphne Jackson Trust.

“I would encourage others to do the same thing despite having been out for a long time.”

Dr Lisa Mohebati is another returner to research at the University of Surrey.

“Contributing to the betterment of the world is important to me. I hope to use the knowledge and experience I have gained in research over many years in many countries to help others,” she says.

“My main interests are in maternal-infant nutrition and health, but I am currently working on a European project which encompasses harmonising measures used across a currently fragmented food consumer science community.

Obesity-related losses of healthy life years and deaths are expected to increase by around 40% from 2019 to 2030 - The Lancet

“My previous research has shown that aspects of parenting are important to breastfeeding outcomes, which other research has shown have implications for later maternal and infant health.

My current research is on what the public believes constitutes “public benefit” from the use of consumer food science data across 5 European countries.

“This is important work because it is novel and provides the views of stakeholders which have previously not been heard, and which are crucial in moving towards healthier and more sustainable food choices.”

She realises her work pokes some complex philosophical issues.

Photo by Chitto Cancio on Unsplash

Photo by Chitto Cancio on Unsplash

“There are always issues around who in fact is able to make healthy and sustainable food choices (i.e. has the time, money, access, knowledge, head space, motivation, social norms, etc.), as disadvantaged populations often do not have these luxuries.”

Lisa married her British husband in 2005 and moved to the UK. .

“At the time I was still working remotely at the University of North Carolina in the US.

“I then started looking for jobs in the UK and ended up finding two part-time jobs in March 2006, one at the University of Sussex with Professor Erik Millstone and one working with Professor Mary Rudolf, a paediatrician from the University of Leeds, who was starting to develop the ideas behind HENRY.

“When my son was nearly two and a half, I looked for another part-time job and got a position as a research assistant at the Brighton and Sussex Medical School woth Professor Anjum Memon.

“It was difficult at first because I missed being with my son. He would go to the University Nursery but I made a point of having lunch with him every day.

“After this, I tried to find other positions but was not successful. Finally, a maternity leave cover came up as lecturer for the Masters in Global Health programme at the Brighton and Sussex Medical school in January 2013.

“I got the job and also discovered I was pregnant. I was offered to apply for a longer term position after the baby's birth but decided to prioritise caring for the baby.

“I worked up until the weekend before I was scheduled for a C-section in August 2013. After he turned 3 and started going to nursery a few hours per day I started looking for another job.

“I missed the mental stimulation, so I began analysing some of my data in order to write a publication.

“It was really hard to do, because I was not connected to any university, so I did not have the access I needed to the articles.

“I also kept looking for other positions that would still allow me to spend time with my children.

“That is when I found the Daphne Jackson Trust.

“It was really hard work, because I needed to write a proposal without having the access to resources available within a university.

“I had always wanted to be a mother, so it was really lovely and fortunate for me to be able to take the time to spend with my children when they were babies.

“But I did miss research and the mental stimulation that comes with it, as well as being able to use my skills, knowledge and experience to further contribute to society.”

"You have a lot to offer the world. It is not always going to be easy, and you may even want to give up. But if you try hard and make the effort, even if a door closes here, a window will open somewhere else, and you will find a way.”

Research impact

Defining research impact could be to say it makes a “real change in the real world.”

In terms of health it means fewer deaths; better quality of life; more effective treatments; reduced costs; or improvements in outcomes.

“Increasing breastfeeding to near-universal levels for infants and young children could save over 800,000 children’s lives a year worldwide (equivalent to 13% of all deaths in children under two) and prevent an extra 20,000 deaths from breast cancer every year”

“In terms of options, nutrition is an amazing field,” says Dr Mohebati.

“It offers such a variety of avenues of work and is of interest not only to athletes, researchers, scientists, health professionals, policy makers and many others but also to regular people on the street.

“Most everyone is happy to talk about food because everyone can relate to it.

“It is a vital issue, part of our day-to-day lives, our social interactions, our culture, our health and well-being; it goes beyond ourselves, our families and friends, affecting many others and their livelihoods in different communities and countries, as well as the Earth itself,” says Lisa.

“Both unhealthy diets and low breastfeeding are huge, multi-factorial public health problems, so addressing them requires concerted collaborative effort on many fronts by many researchers.

“It is hard for me to claim any impact on these things with numbers. However, I am adding my bits to the puzzle on both fronts. In my most recent publication I found that "giving new mothers anticipatory guidance on crying behaviour and a wider array of coping strategies, especially among mothers who expect it to be challenging for them, has the potential to reduce early lactation problems."

Photo by 🇸🇮 Janko Ferlič on Unsplash

Photo by 🇸🇮 Janko Ferlič on Unsplash

“More recently, I have also seen the need to actively involve those whom we are hoping to help in all aspects of the research.

“Thus, to improve the diets and breastfeeding rates of families who are struggling with these issues, they need to be actively on-board.

Photo by Isaac Quesada on Unsplash

Photo by Isaac Quesada on Unsplash

As careers move forward, so does life, and some scientists pause their research careers to accommodate.

But that does not necessarily spell the end of their time in the lab.

“Being the first Nutrition Society-funded Daphne Jackson Fellow was an unexpected honour and I will always be grateful to my supervisors, the University of Surrey, the Daphne Jackson Trust and the Nutrition Society for giving me the opportunity to find my way back to science,” says Lisa.

Her current research project is the EU Horizon 2020 COMFOCUS (Community on Food Consumer Science) project (www.comfocus.eu)

University of Surrey Department of Nutrition

School of Biosciences

University of Surrey

Guildford

Surrey

GU2 7XH

The Daphne Jackson Trust

The Daphne Jackson Trust

Department of Physics

University of Surrey

Guildford

Surrey

GU2 7XH