Disability and Neurodiversity

Celebrating the University of Surrey's diverse community of staff and students

Disability History Month (UKDHM) is observed in the UK each year and here at Surrey we will be marking the month with our second Disability and Neurodivergence Awareness Month to promote a more inclusive understanding of disability and neurodivergence.

Eight members of the Surrey community - staff, students and alumni who identify as disabled or neurodivergent - share their stories.

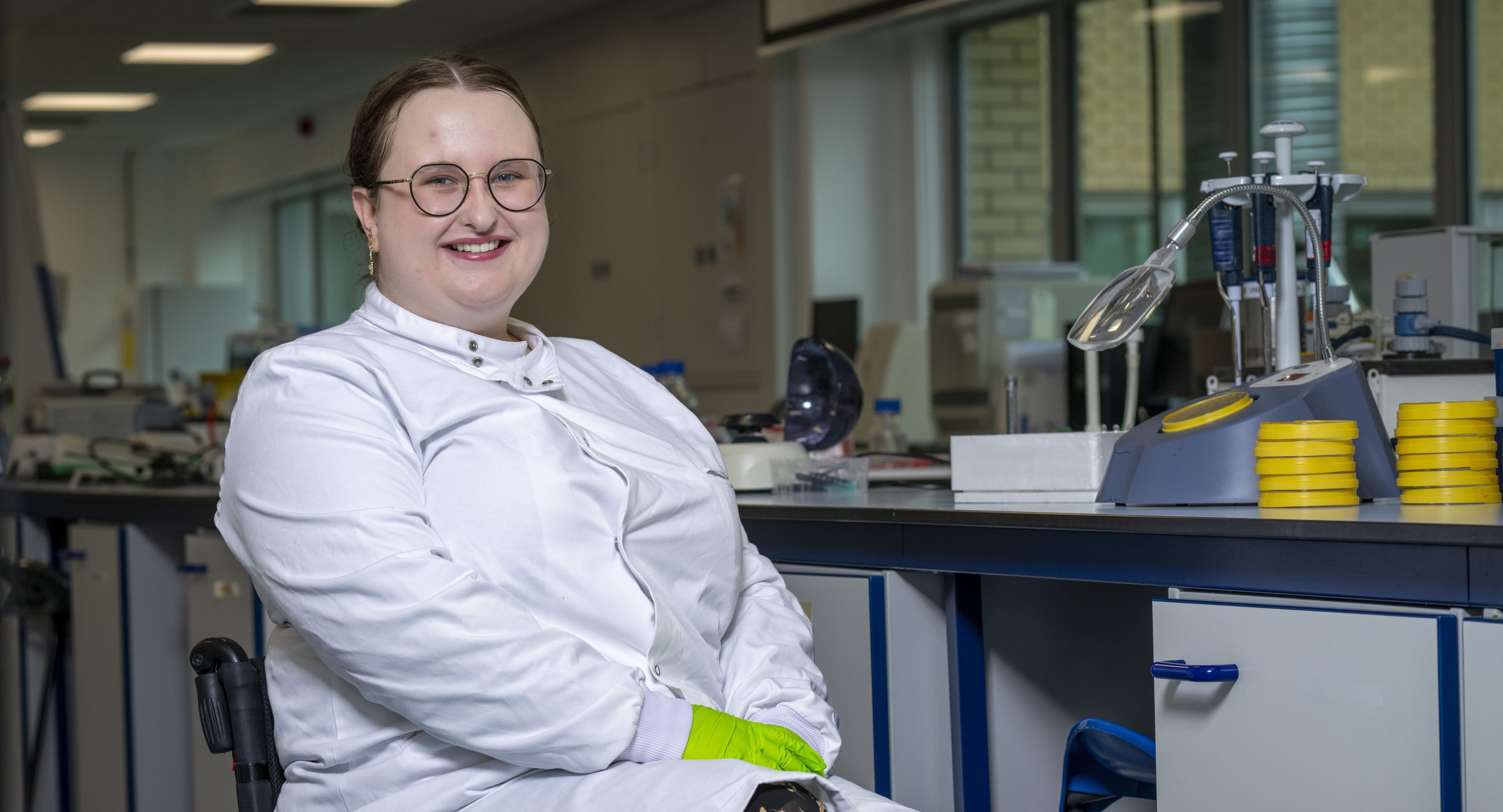

Abi Hayes

Abi is a final-year Biochemistry undergraduate student and disability activist at the University of Surrey. She has been involved in Surrey Students' Union Equality Network and helped establish the University's first Disability and Neurodivergence Awareness Month in 2024.

"I'm a young, queer, disabled person. I have an energy-limiting disability and I use a wheelchair. I spend most of my time in bed, but I have built a lovely online community and I still have a lot of joy in my life.

Living with multiple chronic illnesses has shaped every part of my life. I’ve been diagnosed with hypermobile Ehlers-Danlos syndrome, mast cell activation syndrome, postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome (POTS), inappropriate sinus tachycardia, complex migraines, and a spinal fluid leak that causes low-pressure headaches. But the most debilitating condition I live with is severe ME (myalgic encephalomyelitis). It affects my energy levels so drastically that even basic daily activities can become overwhelming.

I’ve always been a creative person, but my conditions have forced me to adapt. I’ve had to shift my creativity into digital formats - things I can do from bed.

Disability isn’t new to me. My dad is also disabled - he’s a wheelchair user and has lived with similar symptoms like joint pain, fatigue and nausea. Growing up with him gave me a strong understanding of disability rights and advocacy. I never met my grandmother, but I’ve heard she also had many undiagnosed health issues.

I always planned to go to university. I was always academic and got five offers, and got good grades. But that summer, I became reliant on a wheelchair, and I couldn't push my bulky manual one due to joint issues and fatigue, so I spent the summer fundraising £4,000 to buy a suitable wheelchair.

I’d applied to Surrey before I became a wheelchair user, and only realised how hilly the campus was once I arrived. Thankfully, the Disability and Neuroinclusion team were incredible. They checked every classroom for accessibility, arranged coursework and exam adjustments, and even lent me an electric wheelchair from the labs when mine hadn’t arrived yet. That made a huge difference - I could get to class and enjoy being outside."

Bob Nichol

Bob is a Professor of Astrophysics and Pro-Vice-Chancellor and Executive Dean of the Faculty of Engineering and Physical Sciences at Surrey. He joined Surrey in 2021 from the University of Portsmouth.

"I was diagnosed as dyslexic in secondary school back in the 80s. I was doing OK but I couldn't read or spell as well as others, so my mother pushed the school to test me.

Being diagnosed gave me an explanation, and I suddenly went from feeling like an idiot to an understanding of why I was different, and that’s OK.

I am still a slow reader and don’t often read for pleasure. I have learnt to read through pattern recognition so I recognise a lot of words by their letters. Words I don’t know scare me! I just can’t spell or read words phonetically like other people.

My worst nightmare would be being asked to read out the names at Graduation. You may as well give me something in another language because I can't read it. Likewise, if someone writes me a speech for me to read it's terrible; I’m a good speaker but I find it is much easier for me to do it “off the cuff” with a few notes at hand.

Computers have been a huge help and AI will only make it better for me. I struggle to see spelling errors but that’s what computers can do well. Even having the computer speaking text I’ve written really helps me.

To anyone going through their diagnosis journey, either for themselves or for their child, focus on the positives. Remember all the stuff you – or they – are good at.

Whatever disability or neurodiversity or any other sort of perceived difference it shouldn't hold you back."

Emily Boucher

Emily is a Senior MySurrey Hive Assistant, working to support students at Surrey. She joined the University in 2017.

"For years, I didn’t understand why life felt harder for me than it did for others. I’d been through various mental health diagnoses - anxiety, borderline personality disorder, complex post-traumatic stress disorder - but it wasn’t until my son was being assessed for autism that things clicked. Reading about ADHD was like reading about myself. Getting diagnosed and starting medication changed everything - it didn’t dull me, it made life manageable. Now, I help my kids understand that our neurodivergence isn’t something to hide - it’s just who we are, and that’s completely okay.

I’ve been lucky to have incredibly supportive managers and colleagues. When I explained my struggles with time blindness, they didn’t judge - they listened. It’s not about excuses, it’s about understanding. I try to pass that on to students too: you’re entitled to support, and you shouldn’t feel like a burden for asking. I want my kids to grow up in a world where they don’t have to fight for adjustments.

At Surrey, I’ve felt heard. Conversations about neurodiversity aren’t shut down - they’re welcomed. That openness has helped me thrive, and I hope it becomes the norm everywhere, not the exception. Everyone should be treated fairly and things shouldn't be harder because you're poor or gay or neurodiverse or black.

Whenever we have new team members starting, I always let them know that I have ADHD so they understand how I might struggle with things and it makes the relationship easier because they know what to expect. Likewise, if anyone in my team has any disability or neurodiversity, I encourage them to think about reasonable adjustments and how we might be able to support them."

Huw Samuel

Huw has worked in the Marketing and Communications department at Surrey since 2023. He is responsible for producing content for the University's social media channels.

"I was 29 when I was diagnosed with ADHD, and honestly, it came as a complete surprise. I’d never once considered that I might be neurodivergent. I’d struggled with depression in my late twenties and just felt like I was constantly failing at the basics - keeping on top of day-to-day tasks, staying organised, managing time. I was doing Cognitive Behavioural Therapy at the time, and it was actually my therapist who first suggested ADHD might be a factor. I took an online test, then followed up with my GP, and the results were pretty clear - I ticked 19 out of the 20 boxes.

At first, I tried medication, but it completely flattened my creativity, so I stopped. What helped more than anything was simply understanding what ADHD meant for me. That knowledge allowed me to make changes - building routines, avoiding certain triggers and working with my strengths. My wife has been amazing too. She understands how my brain works and supports me in ways that make a real difference.

Getting diagnosed was genuinely one of the best things that’s ever happened to me. It gave me a framework to understand myself. I know now that there are things I’ll always find difficult - but I also know I have strengths that others don’t. I can spot creative solutions others might miss. I can see a winning move in chess that no one else notices. That’s the ADHD brain at work.

I often describe my ADHD as a separate creature living in my head. I’ve learned that I can’t fight it - I have to work with it. When I do, I thrive. When I try to force myself into a neurotypical mould, I fail miserably. Embracing my ADHD means embracing who I really am.

I’ve also learned to be careful. I have an addictive personality, and ADHD can be very all-or-nothing. Gambling, for example, is a no-go for me. I’m not interested in winning £5 - I want the jackpot, and that mindset can be dangerous. I’ve had to steer clear of things like late-night gaming too. Now, I channel that energy into healthier hobbies like metal detecting and getting outdoors.

I used to be embarrassed about my ADHD, but not anymore. It’s more common than I realised, and being open about it helps. People don’t always adapt to how I work, but I’ve found ways to communicate what I need. I don’t use ADHD as an excuse, but I do remind people that it’s part of how I function - especially when it comes to things like organisation.

School was tough. I struggled to focus, doodled constantly and failed a lot of classes. It wasn’t until university, studying media, that I found my place. It was creative, hands-on, and full of people who believed in my ideas. I found my tribe."

Jaden Ogunlade

Jaden is a second-year Adult Nursing student. Originally from Nigeria, she is President of the Korean International Student Society (KISS), a student society celebrating Korean culture.

"I was diagnosed with ADHD and dyslexia about a year ago, after joining Surrey thanks to my Personal Tutor and the Disability and Neuroinclusion team. Looking back, I’d always struggled in school. I’d get the same feedback that I was smart, but easily lost focus and I just accepted that I was forgetful or easily distracted.

The process of getting support was surprisingly smooth. Even from the UCAS application stage, there were opportunities to flag if you might need additional support. My registration was done in a quieter setting, one-to-one, where I could talk about my past learning challenges, which made a huge difference.

Since then, I’ve had support put in place that really helps. Because of my dyslexia, I get extra time and can bring in bullet points for my vivas to help me stay on track. It levels the playing field. On placement, too, having a diagnosis helps me explain how I work best. It’s not just about getting tailored adjustments - it’s about having the language to explain who I am and how I function.

Before my diagnosis, I thought I was just someone who didn’t pay attention. But I’ve realised that when I care about something - like my friends, my patients - I notice everything. I pick up on the smallest details that others miss. That’s my superpower. It’s ironic, really. People think ADHD means you can’t focus, but when I’m passionate about something, I give it my all.

I never really liked school, but at university I'm loving being in education. The campus is so diverse, and I’ve been able to explore different sides of myself. Time management is still a big challenge. I have to plan everything - when I’ll wake up, what I’ll eat, how I’ll get through the day. Things that might seem simple to others, like meal prepping or getting out the door, take a lot of mental energy for me. I’ve had to create systems just to manage the basics.

People often misunderstand ADHD. They think it’s just being hyperactive or bouncing off the walls. For me, it’s often internal - my brain is constantly buzzing, even if I look calm on the outside. That can be misread as being spacey or uninterested, but really, I’m just processing a lot.

Coming from a traditional Nigerian background, mental health wasn’t something we talked about. My parents didn’t understand at first, but since my diagnosis, they’ve become more supportive. I’ve shared videos and explained things, and now they’re starting to see the signs they missed when I was younger.

There’s great support at Surrey, but I think we need more visibility. I only found out what was available because I’m naturally curious and proactive. I've met other students didn’t know help was available. That’s why sharing stories like this matters - so others know they’re not alone, and that support is out there."

Martyn Sandford

Martyn first arrived at Surrey in 1971 to study Physics. He returned to the University in 1989, where he worked in the IT department until 2016.

"After graduating from Surrey, I spent the first half of my career teaching Physics at Godalming Sixth Form College. I loved teaching but found that became sidelined by bureaucracy and issues that had little to do with students or their learning. That’s when I saw an advert for a job at Surrey. The University was transitioning from paper-based records to computer systems, and at that time, there weren’t many ready-made software packages. We were analyst programmers, which meant we did everything; talking to staff, understanding their processes, designing systems, writing the software, training them, and supporting them as they used it. It was personal and efficient, and I loved that.

Back then, the IT department was where the Library is now. It was called the Computing Unit and had two wings - one focused on academic computing for research and teaching, and the other on administrative systems like HR and finance. It was an exciting time to be part of that transformation.

While working at Surrey, I joined a hard-of-hearing group in Guildford and started lip-reading classes. I’d had some hearing loss as a child, but it wasn’t significant then. Over time, though, my hearing deteriorated, and I eventually became deaf. I describe myself as deaf with a lowercase “d” - not part of a deaf community for whom sign language is the main form of communication.

The University gave all the support I could have wished for. HR brought in an Access to Work Advisor who assessed my needs. My main concern was hearing better in meetings. Between them, Access to Work and the University provided equipment like a personal listener - a microphone and transmitter that linked to my hearing aids. It transformed my ability to participate, especially in round-table discussions.

I’ve always been open about my disability, and that openness led me to join a disability panel at Surrey. We represented different disabilities - vision, hearing, physical - and worked to improve accessibility. One thing that struck me during those discussions was how everyone has strengths and weaknesses. Some limitations are accepted as normal, but others are labelled as disabilities. Recognising that spectrum in everyone is important.

One of my key campaigns was improving hearing loop provision in lecture theatres and large teaching spaces. Hearing loops are simple technology - a wire around the room that transmits sound directly to hearing aids, cutting out background noise. When they work, they make a huge difference. But keeping them reliable was a constant battle - AV systems not switched on, presenters not using microphones, or someone accidentally turning down the loop volume*. Still, it mattered because one in six people have hearing issues, and students, staff and visitors deserve equal access."

*Surrey now uses Mobile Connect technology as a means to support assistive listening.

Natasha Winge

Natasha joined Surrey as an undergraduate in 2019. After graduating in Music and Sound Recording (Tonmeister) course in 2023, she is now a part-time lecturer and PhD candidate in Audio Engineering.

"I always wanted to be a classical musician, but also enjoyed programming and maths, so when one of my music teachers at school suggested the Tonmeister course, it was a perfect fit.

For a long time I thought I was autistic, but I didn't necessarily show the stereotypical symptoms that are usually associated with young boys.

About three or four years ago I developed functional neurological disorder (FND). It took nearly two years to get a diagnosis because neurological conditions are complex and hard to pin down. After that, I was referred for an ADHD assessment, and I’m still waiting for an autism diagnosis. I never really thought about ADHD until a friend pointed it out. I was talking to them about autism, and they said, 'that sounds more like ADHD'. So I went to my doctor and rambled for 20 minutes straight. I think that alone convinced them to refer me.

Looking back, the signs were always there. I never had long-term friendships, I jumped between hobbies, and my brain felt chaotic most of the time. Music was my escape - when I played, everything went quiet, and I could just be present. At the time, I thought I just loved music, but now I see it was a coping mechanism. Getting these diagnoses has helped me understand myself and, more importantly, forgive myself. Before, I’d push through and end up burnt out. Last year, I had to take three months off because unmanaged ADHD symptoms and FND left me overwhelmed. Now, I notice the signs earlier, take breaks, and manage things better so I don’t reach that point again.

When I first considered an autism assessment, a friend suggested I speak to the Disability and Neuroinclusion team. I expected them to dismiss me until I had a diagnosis, but they helped put some accommodations in place. That was a huge relief. They arranged extra time for exams and even helped me communicate with lecturers, which took away a lot of stress. When I withdrew last year, they were supportive and reminded me that health comes first. They also gave me a Study Skills Tutor, which was invaluable. Breaking big tasks into smaller steps is something I really struggle with, so having someone guide me through that made a big difference.

My FND started as muscle spasms in my face, hands locking, and sometimes vocal tics. Later, I developed functional seizures, which are non-epileptic but still debilitating. For me, FND and ADHD are linked - when I’m overwhelmed, symptoms flare. At first, I was terrified of people seeing my tics. Mental health symptoms can be hidden, but physical ones are visible. I avoided going out, worried about judgment. My friends helped me through that, and now I remind myself that if someone judges, that’s on them, not me.

The seizures aren’t easy, but my department has been understanding. They know what to do - give me space, let me recover. The Disability and Neuroinclusion team even helped me create an emergency plan, asking what I wanted rather than telling me what to do. That sense of control changed everything. It made me feel heard, respected, and supported."

Theo Donnelly

Theo arrived at Surrey in 2017 to study Politics and Economics. After graduating he was elected as a sabbatical officer in the Students' Union for a year before joining the University as a member of staff.

"Shortly before I turned six, I had a virus which caused transverse myelitis - an inflammation of the spinal cord, which left me with nerve damage and unable to walk.

As a result of being non-weight-bearing, I also developed osteoporosis and scoliosis. I don’t remember much before that, which probably made it easier to adapt. I think it’s harder for people who become disabled later in life after playing sports or being very active.

I missed a lot of school that first year, but eventually returned to my local primary school. Later, I went to a secondary school over an hour away that had a specialist unit. I attended mainstream classes for subjects like maths and geography but had access to physio, a hydrotherapy pool, and a Learning Support Assistant who took notes for me. I can write a little, but not quickly, so all my exams were scribed.

Being a wheelchair user, I visited a lot of universities beforehand, and accessibility varied hugely. Surrey’s campus isn’t perfect - it certainly has its quirks - but compared to others, it was much better, so I chose to study here.

While I was at University I had 24-hour carers, which took some organising, and I got a discount on accommodation in Twyford Court. Initially, someone was meant to take notes in lectures, but they pulled out in the first week. Luckily, I’d made friends who were happy to share their notes, and the University paid them for it, which worked well for everyone. For exams, I had a separate room and scribes. Over time, things improved - lectures were recorded, learning materials uploaded online. I think if I’d gone to university 20 years ago, it would have been much harder.

In my third year, I became Union Chair, a part-time officer in the Students’ Union, and after graduating, I was elected as VP Voice. That year was strange because it was during the pandemic - sometimes we were on campus, sometimes in lockdown.

I joined the University staff in a student-facing role and now work in the Faculty of Arts, Business and Social Sciences.

As a staff member, my experience has been positive. I’ve had several managers, all supportive - sorting electric doors, adjustable desks, and understanding practical needs. For example, I don’t come into the office as much when it’s really cold because poor circulation makes my legs cold.

Throughout my time at Surrey - both as a student and staff member - I’ve advocated for disability support. I helped establish the Purple Network and worked on getting ramps installed and lifts fixed. Accessibility matters, and I wanted to make things better for those who come after me."